Celebrating Buffalo’s Black American History

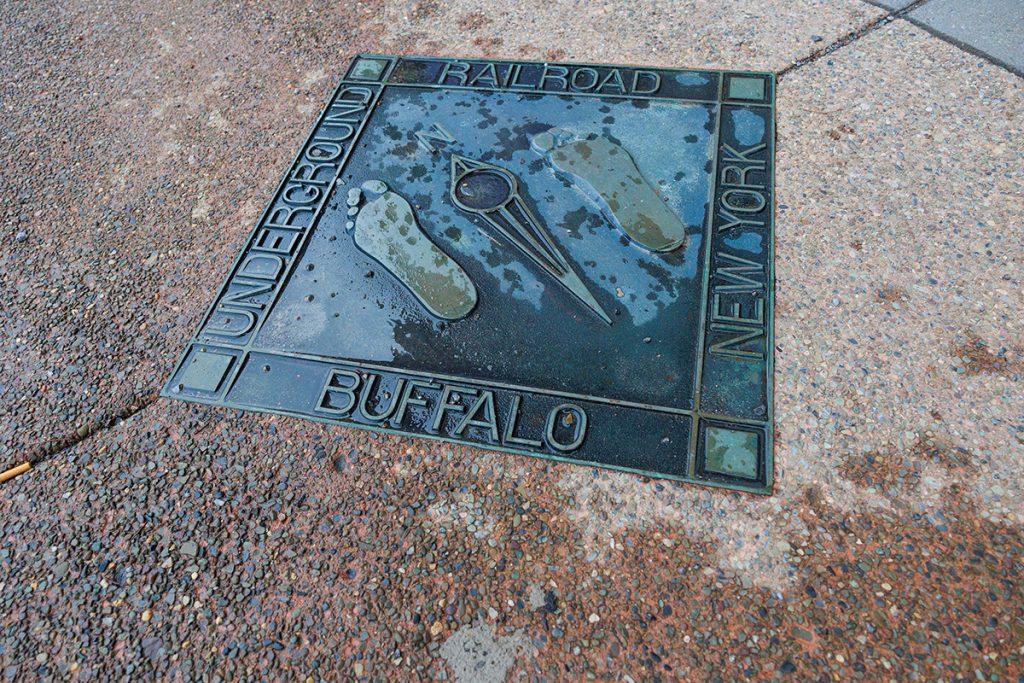

Buffalo, a waterfront city on the border with Canada, has long been a central hub of civil rights history in America. That legacy, long ignored and forgotten, is newly celebrated in the heart of downtown: The Michigan Street African American Heritage Corridor, with updated, renovated, and expanded buildings debuting this year, is now a place where civil rights history comes alive.

People can visit the church built in 1845 by African Americans who helped people flee enslavement through the Underground Railroad. Walk through the house where the church’s pastor, a founding NAACP member, lived with his family for decades. Hear his Victrola play, see the typewriter where he wrote his sermons, and understand how he brokered power in his decades long career. Round the corner to the Black musicians’ union clubhouse and museum where Aretha Franklin, Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillespie, and John Coltrane ate, drank, and performed during segregation. A new, developing museum of radio history will share the stories and voices of Black political activists who were not heard on most radio stations in the 1960s.

“You know, you don’t have a lot of other places in the country where you have African American-specific museums, culture and arts … within steps of one another,” said Terry Alford, executive director of the Michigan Street African American Heritage Corridor Commission. “And, of course, it served as one of the catalysts in the country for this new art form called jazz.”

The stops in the Heritage Corridor reveal a past that has been neglected but is now being celebrated.

Michigan Street Baptist Church

511 Michigan Avenue, Buffalo, NY

The Michigan Street Baptist Church, built for and by Buffalo’s Black residents, was a final stop on the Underground Railroad to freedom in Canada, and a meeting place for organizers of the civil rights movement. Led by Rev. J. Edward Nash Sr., it was a place where Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist and orator, and W.E.B. Du Bois, a sociologist and activist, came to speak. Founders of the Niagara Movement, the forerunner of the NAACP, met there. Step into in the building with tall windows rimmed in colored glass and see where progressive social history lives on.

The Nash House Museum

36 Nash Street, Buffalo, NY

The Nash House is a time capsule and museum of the history of Rev. J. Edward Nash Sr., who served as pastor of Michigan Street Baptist Church from 1892 to 1953. Located just behind the church, it’s filled with the things that he touched and used every day, like the vintage-equipped vintage kitchen and desk and books. The church, his home, and the home of neighboring parishioner activist Mary Burnett Talbert, since torn down, were meeting sites for local and national civil rights activists. Nash and Talbert helped the Niagara Movement get started as W.E.B. DuBois organized a series of meetings in Fort Erie, Ontario, in the summer of 1905.

The Colored Musicians Club & Jazz Museum

145 Broadway, Buffalo, NY

In the early 1900s, Buffalo’s Black musicians were banned from joining the all-White union Local 43 of the American Federation of Musicians. In response, they formed their own union, the Local 553, in 1917. The next year, its members created the Colored Musicians Club, a social club where musicians hung out, ate, drank, practiced, and joined impromptu jam sessions along the well-worn wood bar that stretches the length of the upstairs club. The Colored Musicians Club & Jazz Museum is the only continuously running, all-Black-owned music venue in the nation, and a tribute to jazz and Buffalo’s impact as a place where people, like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald and Dizzy Gillespie came together and music evolved.

WUFO Radio Station & Black History Collective

143 Broadway, Buffalo, NY

Established in 1961, WUFO was the first radio station with programming for Buffalo’s Black community. In 1998, sales manager Sheila Brown quit because the station’s owners “did not treat the community properly.” In 2006, she returned to the station and became general manager. In 2013, she bought it and became the first Black woman to own a radio station in Western New York. WUFO, 1080-AM and 96.5 FM, airs classic hip-hop, urban adult contemporary music, and community talk shows. In 2018, Brown launched the Black History Collective, a museum that celebrates the station’s history and connection to the civil rights movement.

“Each one of these entities are basically now serving as museums,” Alford said. “Buffalo represents about 185 years of the African American experience right up until today.”